Day One is ending for Amazon. Now what?

For more than 20 years, Jeff Bezos fought against the entropy inherent in large organizations. He demanded that Amazon always act as a startup, that it would always be Day 1 at Amazon. As he said in his 1997 shareholder letter, “Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death. And that is why it is always Day 1.”

For many years, Bezos won. Amazon remained agile and entrepreneurial, with structures, processes, and personnel that served the great god of growth. For decades, Amazon revenues grew at 20% or better every year. What an accomplishment! What Bezos did with Amazon was unique and extraordinary.

But despite every best effort, the sun does set. Now Bezos is gone, and Day One is ending. In fact, it is Amazon’s extraordinary success that dooms Day 1.

Amazon is now a behemoth, with revenues of $470 billion in 2021. Companies that size simply cannot grow at 20% for ever. In fact, they cannot do it at all if they are engaged with the physical world. Walmart grew less than 4% last year. Target has been highly successful recently, and grew 13% in 2021 – but it’s only a quarter the size of Amazon. Amazon cannot just look behind the sofa and find another $100 billion in new revenue. If by some miracle it did so, that would just impose even more crushing demands the following year. This level of growth at this scale is not sustainable.

So Amazon is transitioning from startup to behemoth. And for the last five years at least, it’s been a badly misguided transition, as Amazon acts as a strategic ostrich, trying to avoid the unavoidable. It found billions in revenue by growing an enormous advertising business. It opened bricks and mortar stores. It tried to get into healthcare. It threatened to become the next FedEx. It entered increasingly difficult online niche markets. It even tried to get into fashion. These initiatives reflect what I call a “growth panic.”

For a time, these growth initiatives worked. They seemed to reflect the manifest destiny of Amazon’s inevitable march across the economic landscape: it looked like Amazon could not be stopped. But the reality is different. After the massive distortion of the pandemic and lockdown is removed, Amazon’s profitability is clearly sliding, largely because its retail business has grown too fast and too far, creating a vast lake of red ink (documented closely in my book about Amazon). That incredible retail business has now become the millstone dragging down the company.

The lake of red ink at the heart of Amazon retail results directly from Amazon’s desperate hunt for the revenue growth needed to sustain its membership in the great FAANG family of high growth companies (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google). Investors in growth companies buy today on the promise of bigger profits tomorrow. And each of the other FAANG companies has delivered (leaving aside Netflix, a special case): each now sits on a gusher of profits. Except for Amazon, which has used revenue growth to cover for out-of-whack fundamentals.

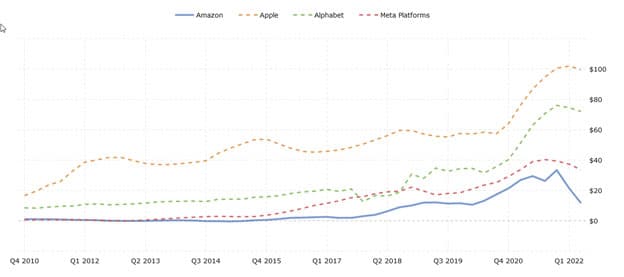

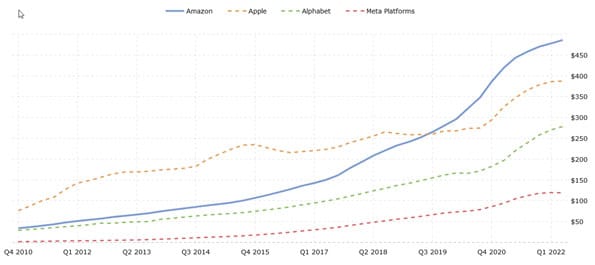

The story is simply told in two charts: Amazon blasting past competitors in search of more and more revenues – and falling further and further behind in operating income. The promise of future profits is breaking, and investors are noticing.

Net income

Revenues

Source: Macrotrends

Apple’s price to earnings ratio is currently around 20. Google’s is 19. That’s understandable for a growth company. But Amazon’s is over 100, partly because its profits are relatively low and partly because it is still seen – despite some slowing revenues – as a growth company. That’s helpful operationally, as Amazon’s growth still terrifies competitors, but the real meat is in Amazon’s valuation and stock price: growth companies are valued more highly – FAR more highly – than standard retail companies.

Because Amazon was built as a growth company, it could pay its white-collar workers – especially its tech workers – below average wages, using stock options to compensate. All FAANG companies do that, but Amazon relies on stock more than most. That works well when the stock prices is booming. CEO Andy Jassy received $175,000 in cash in 2021, plus 61,000 stock options that vest between 2022 and 2031, ostensibly worth more than $200 million. A great payday for him. But what if those stock options become worthless, if the stock price falls? Amazon has already started to change compensation toward more cash and less stock. But that’s not enough, at least at AWS: tech workers want the upside offered by options. That’s how they become rich, instead of just well paid.

So Amazon is in a bind. Realistically, it cannot find the next $100 billion: growing revenues is hard and at that scale increasingly impossible, even for Amazon. But the search for growth itself has undercut profitability, leading Amazon into all kinds of blind alleys. Flattening growth and declining profitability is therefore becoming a perfect storm.

What’s next after Day One?

Essentially, Amazon must transform from a wildly successful startup into a mature and successful business based on its still-powerful core competitive advantages. Fortunately, it has an enormous and profitable suite of related businesses, which can be the base on which to build an extraordinarily successful and profitable company in the coming decade, if Amazon is prepared to do the hard work: focusing on what is profitable, eliminating what is not, and casting aside the fantasy of exponential growth today, growth tomorrow, growth forever.

That shift in paradigm has multiple implications:

- Cutting back on its first-party online retail business. Amazon’s panic for growth has led to some ridiculous initiatives online – Amazon as a high fashion retailer anyone? No? Amazon started in the sectors best suited for online disruption – books, toys, electronics. Every additional sector has been slightly less advantageous. So the search for rapid growth in online retail has led to huge losses. Those loss-leading segments are already being cut back, retail executive hiring has been frozen, and that pruning will accelerate quickly. Rationalizing its own retail business is the central key to profitability for Amazon, because this is where all the red ink lives.

- Fewer big adventures. The leap into health care has not gone well, the drone delivery project is on its last legs, and in general Amazon will be less cavalier about investing billions in chancy projects focused on explosive growth potential. It will buy companies strategically to support its supply chain, or to expand its market, and it will still make some big investments, but Quixotic ventures like these should face much tougher screening.

- Eliminating bricks and mortar stores. Amazon is still building out its brocks and mortar grocery business, but realistically, this has no standalone future (Amazon may successfully license some of its related technology). Amazon won’t buy a big chain to make itself a real competitor in groceries, and it cannot grow a grocery chain to scale even at double its current rate of expansion. Worse, it has no competitive advantage over deeply entrenched, highly efficient, and much larger competitors – as results from Whole Foods demonstrate five years in, where revenues remain flat. The less said about idiotic money pits like 4-star stores and Amazon bookstores the better.

- Spinning off AWS. The government cannot force an AWS spin-off through anti-trust. But strategically, AWS no longer needs Amazon to be its first and best customer – it has many others now – while at the same time Amazon can easily buy all the tech services it needs from an independent AWS. And AWS staff and executives won’t forever continue to accept stock options that are tied to low-growth retail. So while a spinoff is far from inevitable, it is beginning to make business sense. Amazon will just have to be careful about what it does with $1 trillion or more in cash that results.

- Focusing on the Marketplace. Amazon’s future core retail business is the Marketplace for third-party sellers, not its own online retail. The Marketplace is hugely profitable and faces no significant barriers to further growth – at least in the US – except Amazon’s own missteps. It’s also the source of most advertising revenue, and it drives Prime membership. But as the Marketplace becomes the shining star of the Amazon ecology (especially after AWS is sold) Amazon will need to manage it that way: treating its vendors much better (which costs money), cleaning up its own missteps (e.g. creating a direct pathway from Chinese manufacturers to US consumers, as well as growing malfeasance on the platform); and reversing UX mistakes (ads now overwhelm the front search page, because they are immensely profitable and Amazon needs those profits to cover for retail losses). The customer experience has suffered badly as a result, and that needs to change.

- Accepting that private labels are generally more trouble than they are worth. According to Amazon’s own Congressional testimony, its private labels have been a disaster (not entirely sure why, given that white labels work for Walmart and Target). Most will likely be gone within 5 years, as that’s an easy way to make regulators happy and also to improve the bottom line, though a handful of segments will be retained – batteries and low-end apparel for example.

- Rebooting international (which has also been part of the panic for growth). Maybe Amazon will follow its path out of China elsewhere – in India for example, and other markets where it faces tough domestic competition. Amazon international revenues were up 22% in 2021 – while operating income slipped from 0.6% to -0.7%. Amazon doesn’t need endless international expansion, which is hard to pull off; for example, in parts of Europe it’s illegal to simply leave an unattended package, so Amazon’s US delivery model doesn’t work.

- Rethinking delivery. Amazon used extremely rapid delivery as a club to beat down competitors. It is hard to match 2-day delivery, 1-day is harder still, and same day is just a money pit. But Amazon faces those costs as well; while Marketplace sellers pay for their own shipping, Amazon has to pay shipping for its own retail business, so the bigger its retail business, the higher its shipping costs (logistics costs are now 32% of sales, up from 18% ten years ago). Closing some warehouses and limiting the growth of same day delivery nodes is just a start. Amazon must decide what customers really need – and will pay for – and trim away the excess costs beyond that, although reducing the weight of its own retail business will certainly help.

- Stock reset. Amazon stock is down by about one third from its peak. Once the stock has reset to a level that makes sense for an online retail platform (after AWS is spun off) the stock can find a new base level from which can grow. At that point stock options become useful again.

Many of these changes have already started. Amazon has dumped expensive experiments in health care, has cut back on the growth of warehouse capacity and is even closing some facilities, has raised the price of Prime quite sharply (a move which effectively flows 100% to the bottom line), is closing its bookstores and 4-star stores and looking hard at groceries, and is apparently ending its work on delivery drones.

All these shifts point to a change in paradigm. Amazon cannot simply pretend that it is a growth company. Outside AWS, that can be true only to the extent that it moves away from its own retail business, and even then, future growth won’t match previous rates. So the fantasy that “It’s always Day One” must be replaced by joined-up long-term thinking about the nature of the business, what it is and especially what it isn’t, what kinds of innovation and growth make sense, and how to create a profitable and sustainable business in the long term. Jeff Bezos left at exactly the right time for him, because the Day One company he wanted to lead is dissolving under his feet. The question now is whether Andy Jassy is brave enough to grasp the nettle, see that the end of Day One does not mean that it’s Day Two, and build for the long term on what Amazon is really good at: being a platform to deliver the world to customers brilliantly, efficiently, and in the end profitably.

Written by Robin Gaster Ph.D.

Have you read?

3 ways to innovate despite any pending recession by Francesco Fazio.

Investing in Sustainability – Violations of the Sole Interest Rule or Good Business by Dr. William Putsis.

SMAC QR Code to Tap into New Business Opportunities by Dr. Rudy Cardona.

The 3 stages of onboarding that every manager needs to know by Brad Giles.

3 Strategies to Build Your Company’s Resistance to Economic Upheaval by Terry Howerton.

Add CEOWORLD magazine to your Google News feed.

Follow CEOWORLD magazine headlines on: Google News, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook.

Copyright 2024 The CEOWORLD magazine. All rights reserved. This material (and any extract from it) must not be copied, redistributed or placed on any website, without CEOWORLD magazine' prior written consent. For media queries, please contact: info@ceoworld.biz