China is running out of bridges

For many years, China’s GDP growth has been supported by large public investments in infrastructure, but China’s government now quickly needs to find other solutions.

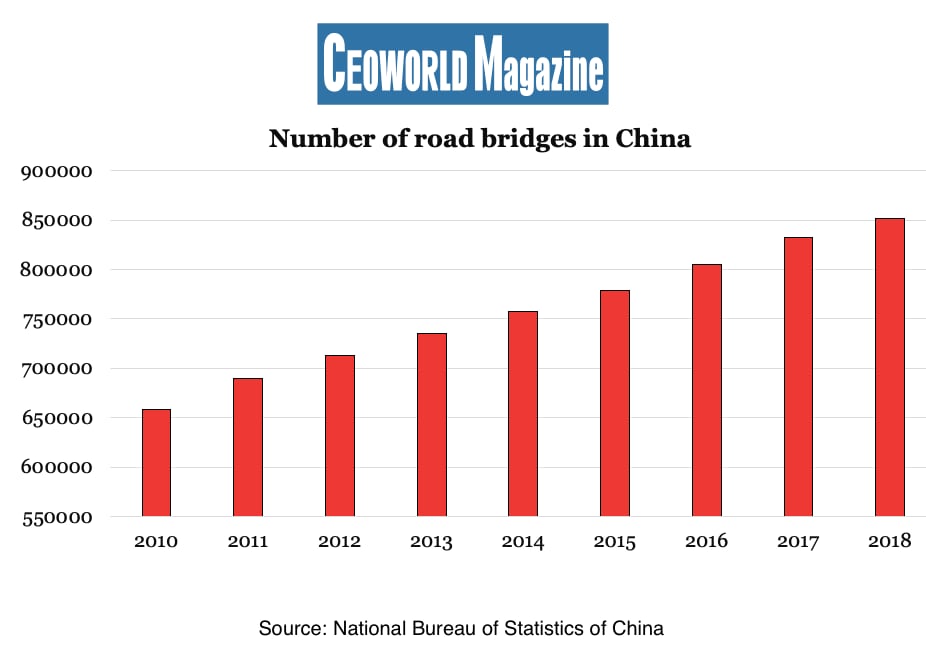

The number of road bridges in China has increased from 658,000 in 2010 to 851,000 last year (graphic one). This development also well describes the overall infrastructure development in the country. Translated into the national account language, these are the significant and famous construction investments that have kept the GDP growth rate up for decades.

If one observes the development in the road bridge construction, the tendency has been that a fewer number of bridges is built per year since 2010. And now, the investments in infrastructure have been going on for so many years that China is lacking bridges to build. At least those that make economically rational sense to construct, and the same applies for other infrastructure projects.

Graphic two shows how the annual lending growth rate in China is declining this year, where several economists point out that fewer loans for infrastructure investment are in demand. The financing is often done via special purpose vehicles in provincial or regional levels, where the profitability of the projects is also part of the equation; for example, a positive yield from the projects has an importance.

In parallel, I note that the annual real estate developers land sales in the provinces continue to decline, though the rate is still positive. There is no direct correlation between construction investments and sales of land, except that both are income generating due to the tolls from the roads, bridges etc. However, I regard both developments as structural and long-term changes, which is why it has a major impact on China’s economy.

Does this trend mean that China’s GDP growth rate is heading even further down? It is a central question, but even more central is whether the Chinese economy can change so drastically, that it can compensate for road bridges that no longer pays off to build, if economic rationale decides. Undoubtedly, this will increasingly concern a number of economists, and for investors in general, the theme is also worth giving attention.

In all emerging economies, investments in infrastructure is extremely valuable for future economic growth, like how the first road or railway from A to B changed trade significantly. But as the economy evolves, the marginal profitability of more infrastructure drops towards zero, or might even be negative. For public investments in infrastructure, it also applies from a rational economic point of view that investments must yield a positive return. It cannot always be measured accurately, but sensible calculations can be made and gives a reasonable indication of returns on infrastructure investments.

Exactly the same considerations apply to the infrastructure expansion in China. The country is huge and there are still countless places where infrastructure is lacking, but for example, the bridges that now remain to be built are less yielding, according to the above considerations.

I still expect infrastructure to be built in China, and some projects will make more sense than others. The same happens in many other countries, where the importance for the country’s GDP growth plays big a role. Though if China will try to keep the GDP growth at the six pct. mark based on unprofitable bridge constructions, then I consider it as negative.

China’s GDP growth is responding extremely fast to public infrastructure investments. So as early as this fourth quarter, it can already be revealed whether the government is choosing the worrying path of simply increasing its capital investment in infrastructure– or do it right.

In my opinion, one of the key points from the described development is that China’s economy is undergoing a structural change due to the change in the value of public infrastructure investments.

Another structural change that especially applies to the provinces is a risk to explore a slump in their revenue from the sale of land to property developers, however, I think the challenge has a longer time horizon. But most likely, this development will generate a downwards pressure on the revenue for the provinces for good. Therefore, I argue that this is also a structural change in the revenue base that occurs over time, and where a partial income/economic growth compensation must be found.

What is really interesting is whether China can create positive structural changes in the economy that can compensate for the fewer bridges that will be built in the future. Undoubtedly, a solution to the trade conflict with the United States will result in more optimism among Chinese manufactures. I would imagine it to trigger renewed investment appetite, though it won’t be a strong reversal. All in all, a further drop in the country’s GDP growth rate might be delayed in the short term, but this is probably also the maximum positive effect coming from ending the trade war.

Several years ago, China’s leadership saw this development coming and tried a new growth path consisting of reforms combined with a greater focus on increasing private consumption. Some reforms have been good and have contributed to a more flexible economy, which in turn creates a better foundation for economic growth.

Yet, the reforms have not been significant landmark achievements, and I regard them as contributing to a long-term structural positive change.

A superior reform, such as the significant tax cut for middle class-income earners last year is worth noting. This contributed to increased private consumption during this year, but big reforms where a control element is abandoned, I hardly can imagine.

The consequence is that the reforms will primarily have economic redistributions in focus, which may well be a fiscal spending to the benefit of private households. I pay extra attention to such possible developments during the next three months, but if nothing happens, investors will react negatively.

What’s certain is that reforms should not simply be small changes. Beijing must come up with exciting proposals to counteract the structural changes that are putting a sustained pressure on the GDP growth.

The result of the tax reform from last year is that 80 million people in China now no longer pay income tax- here, the easy and also exciting solution could be to further reduce income tax, so even more people are exempted from it.

Graphic one: Number of road bridges in China

- 2010: 658100

- 2011: 689400

- 2012: 713400

- 2013: 735300

- 2014: 757100

- 2015: 779200

- 2016: 805300

- 2017: 832500

- 2018: 851500

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

Graphic two: China – Yearly growth rate in lending (in pct.)

- Oct-18: 13.1%

- Nov-18: 13.1%

- Dec-18: 13.5%

- Jan-19: 13.4%

- Feb-19: 13.4%

- Mar-19: 13.7%

- Apr-19: 13.5%

- May-19: 13.4%

- Jun-19: 13%

- Jul-19: 12.6%

- Aug-19: 12.4%

- Sep-19: 12.5%

Source: People’s Bank of China

Have you read?

# Best CEOs In The World 2019: Most Influential Chief Executives.

# World’s Best Countries To Invest In Or Do Business For 2019.

# Countries With The Best Quality of Life, 2019.

# Most Startup Friendly Countries In The World.

Bring the best of the CEOWORLD magazine's global journalism to audiences in the United States and around the world. - Add CEOWORLD magazine to your Google News feed.

Follow CEOWORLD magazine headlines on: Google News, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook.

Copyright 2025 The CEOWORLD magazine. All rights reserved. This material (and any extract from it) must not be copied, redistributed or placed on any website, without CEOWORLD magazine' prior written consent. For media queries, please contact: info@ceoworld.biz