Think Like an Entrepreneur: Earnings Per Share vs EMVA

I have led and taken three companies public, two of which I started. This means that I have had one foot in the world of institutional leadership and another in the world of entrepreneurship. Both are important, but the latter provided me with the greatest lessons on value creation.

Making Your Company Worth More Than It Cost

Most of the world’s businesses are worth no more than they cost to create. Simply put, the equity value of most companies does not exceed the sum of proceeds from equity issuances, together with the cash flow reinvested in the business over time. Assuming you break even, leading a company worth what it cost to create, then your returns over time have equated to your cost of capital. Given enough time shareholders can accumulate wealth, potentially getting rich from such enterprises. But true corporate wealth creation (or showering investors with money created from thin air) does not happen until your company’s business model propels you to produce returns exceeding your cost of capital. In business, it is the excess return, and not the appreciation of underlying business assets, which creates value from thin air. This is almost universally how the richest people throughout history got that way.

Cost of Capital

A lot of attention is paid to cost of capital. Financially speaking, it is the weighted cost of borrowing and lease proceeds, together with the cost of equity. Over my career, I have frequently seen leaders incorrectly compute this number. Oftentimes, they exclude lease proceeds on assets they might have otherwise owned. Likewise, leaders of public companies are often guilty of believing their cost of equity capital to be reflected by an earnings to price ratio. For sure, that is the immediate cost of equity, but hardly equates to investor expectations. Moreover, earnings is a number based on accounting conventions rather than financial realities. Finance, like music, is a universal language, whereas the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) is hardly a universal language. Over time, finance wins.

As I was leading our first public company, I became a disciple of Economic Value Added (EVA), a notion introduced in the 1990’s by G. Bennett Stewart. EVA is the amount of value created by a company in any given year above its cost of capital. At its simplest, you would subtract from your operating profits, expenses pertaining to interest, lease and shareholder returns. Anything left over was EVA. Then, presuming you created a company worth more than it cost, that amount would be called Market Value Added (MVA). Essentially, MVA is a result of EVA creation over time. This construct has since been adopted by shareholder advocates, including Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), in evaluating public company performance.

Equity Market Value Added

As a CEO, I decided that my primary focus should be on the cost of equity. Focusing on shareholder equity would not lessen attention to my cost of capital, since one way to make my shareholders better off was to improve my borrowing and leasing costs. Anyway, the costs of our borrowings and leases tended to be rangebound and had a relatively modest impact on shareholder equity returns. But the biggest reason for this shift in focus is obvious: Shareholders are the prime beneficiaries of MVA. I wanted to make them rich.

In focusing on my cost of equity, my goal became to generate shareholder returns that exceeded the cost of shareholder capital. I then created The Value Equation, a simple six variable formula, to determine current corporate pretax shareholder rates of return. Unlike the notion of EVA, which delivers an absolute number, I was interested in easy-to-compute relative relationships. To the extent that I could deliver shareholder returns that exceeded our cost of equity, then I could make equity worth more than it cost. The amount of that value created over time would be Equity Market Value Added, or EMVA. In determining the weighted average age of our equity, I could also compute compound annual EMVA growth. I wanted to deliver solid EMVA creation and compound annual EMVA growth relative to other public peer companies.

Earnings Per Share vs EMVA

I believe EMVA growth to be better long-term business evaluation metric than a simple focus on compound earnings growth. Between 2015 and 2019, Walmart, amongst the most valuable publicly traded companies and the single largest retailer and corporate employer in the US, threw off close to $30 billion annually in free cash flow from operations. The company paid out only about 20% of that in shareholder dividends, which means that about 80% of annual shareholder cash flows were available for reinvestment into the company each year. Assuming Walmart reinvested the money profitably into its business, how could earnings per share fail to go up? Really, the company could have lit on fire half of its annual retained cash flow, reinvested the other half into earnings-producing investments, and net income per share would be expected to rise.

The reinvestment of cash flows is the main reason that broad stock market indices rise over the long term. They have to. Yet, for shareholders, the paramount issue should be whether companies are able to retain and reinvest their free cash flows without losing any of the value of that reinvested cash. And while not losing any wealth would be great, creating added EMVA would be even better.

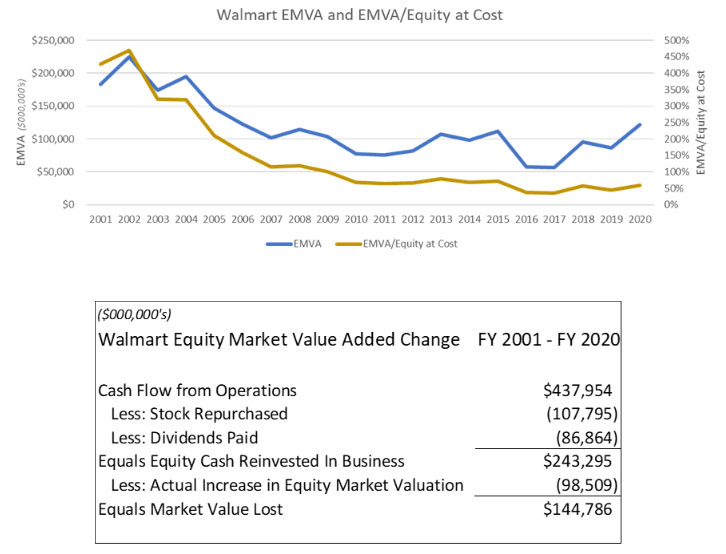

It turns out that Walmart has experienced extensive periods of lighting its free cash flow on fire as earnings per share rose. Over a twenty year-period between its 2001 and 2020 fiscal years, the company effectively lost $145 billion in value on its way to delivering a compound annual rate of returns to its shareholders just below 6% annually. Unfortunately, the delivered returns fell below the company’s cost of equity capital, resulting in EMVA erosion. Between 2001 and 2020, Walmart’s EMVA as a percentage of its equity at cost fell from approximately 615% to around 60%. The company, once an iconic creator of value and leading disruptive retailer had itself fallen prey to competitive pressures from new disruptors.

Value Creation Accountability

Walmart, like virtually all successful companies, initially had a potent business model capable of delivering returns exceeding investor requirements. The result was the creation of a virtual guyser of wealth. The 2021 Forbes 400 list of richest Americans counts seven of its members from the Walton family who collectively continue to own approximately 50% of the storied company.

Growing successful companies are nearly all characterized by EMVA creation. Entrepreneurs absolutely understand this dynamic. Without the ability to harness potent business models that deliver returns exceeding their cost of equity, the companies they lead would likely never have existed. Later, as companies mature and markets change, EMVA delivery invariably becomes more challenging.

A key question to be answered of seasoned companies is the degree to which any EMVA losses are defensive. In other words, might Walmart’s shareholder returns have been worse had the company instead elected to raise shareholder dividends rather than invest some or all the $243 billion back into its business, only to suffer an enormous $145 billion value loss over twenty years?

Corporate CEO’s, especially those of public companies, are often evaluated based on balance sheet and earnings per share growth. But, as custodians of shareholder equity, those metrics should be accompanied by attention to EMVA creation. Growth without value creation suggests a company that is no better than average. Basically, investors could have reinvested the cash themselves into a broad equity index and realized approximately the same rate of return. The challenge for CEO’s is to direct and adapt company business models while being accountable to shareholders for the value created and lost.

Written by Christopher Volk.

Have you read?

Four Advanced Skills for Conflict Resolution and Motivating Others by Stephen McGarvey.

3 Strategies for Working Natural Language Processing Into Your Operations by Rhett Power.

Amazon’s new retail business model: customers win, competitors lose, and sellers pay to play by Robin Gaster Ph.D.

Why Your Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Initiative Isn’t Moving the Needle – And Ways to Spur Movement by James T. McKim.

CEO Spotlight: Mark Hauser Details How Private Equity Transactions Work.

The Best Tech CEOs – Tough, without Acting Tough by Pete Devenyi.

Bring the best of the CEOWORLD magazine's global journalism to audiences in the United States and around the world. - Add CEOWORLD magazine to your Google News feed.

Follow CEOWORLD magazine headlines on: Google News, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook.

Copyright 2025 The CEOWORLD magazine. All rights reserved. This material (and any extract from it) must not be copied, redistributed or placed on any website, without CEOWORLD magazine' prior written consent. For media queries, please contact: info@ceoworld.biz