How Can Organisations Debias Their Decisions?

People whose personal details and experiences signal they come from racially diverse backgrounds are less likely than whites to make it through the first cut in recruitment processes. Even if the organisation says it values diversity.

A strategy adopted to beat the system is to ‘whiten’ information, and this makes it more likely to get past that first hurdle or two. And recent research shows that when individuals believe the rhetoric of diversity-friendly organisations and therefore don’t whiten their resumes, they are less likely to be selected than those who do. Another damned if you do, doomed if you don’t scenario that shows how difficult fairness is.

Yet we have made some progress. Since the early 2000s, awareness of how easily unconscious thinking biases decisions has grown enormously. It was believed that associations couldn’t be changed without a major but non-guaranteed reprogramming effort. Since then we’ve learned that the associations do change in other ways, but more importantly we know that if we shift the focus to improving decision-making processes we can get a better payback on effort.

A growing list of what doesn’t work might seem frustrating, but it stops us from continuing to make the same mistakes and that has real value. We know that command and control approaches, adopted by many organisations, backfire. You can’t get people to change by telling them to. And you don’t get people to change by blaming them for doing the wrong thing. Making training about beliefs and preferences mandatory is almost guaranteed to fail. That’s because suppressing unconscious beliefs, to ‘do what’s expected’, is well-known to make bias more, not less, likely. And the danger is that in these circumstances biases may increase rather than decrease.

It’s not enough to be committed to making fair decisions

Even when managers and decision-makers espouse a commitment to gender equality and a desire to promote more women into leadership positions, they are prone to evaluate women less positively.

Women are commonly demoted to traditional gender roles. Forty-five percent of women in one study have been asked to make the tea in meetings. Some were CEO at the time. Female doctors are often mistaken for nurses, female lawyers for paralegals and female professionals of many kinds for personal assistants.

Student evaluations of teaching appear to be influenced similarly. Even in an online course where the gender of the instructor was manipulated so that identical experiences were provided to students, those students who believed they had a female teacher provided significantly lower teaching evaluations. While these lower ratings misrepresent actual competency, they nevertheless may create a self-fulfilling prophesy where women’s career advancement choices begin to conform to the stereotype. And erroneous beliefs about women’s competency levels limit the opportunities that are provided to them; the misrepresentations are perpetuated.

How to debias decisions

By deliberately analysing and structuring how information is conveyed and options are presented, it can become easier to make fairer decisions.

Johnson & Johnson, which fields about 1 million job applications for over 25,000 job openings each year, now uses Textio to debias their job ads. When they first started using it they found that their job ads were skewed with masculine language. They were disproportionately valuing male characteristics. Their pilot program to change the language in their ads resulted in a 9% percent increase in female applicants.

Anonymous processes are the most effective at debiasing evaluations of people. There’s been a surge in the use of automated recruitment tools for debiasing, but they aren’t perfect either. They may simply be making it easier to make the same mistakes, while masquerading as fair and objective. Experimentation is the order of the day. Run processes in parallel, be curious about where you can intervene in your own processes to get the best outcomes.

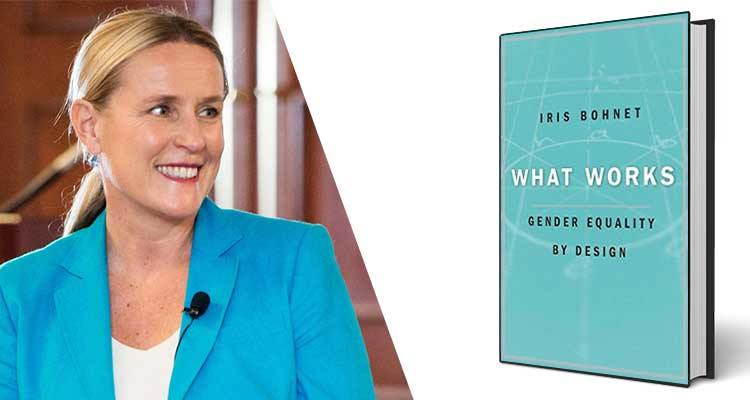

To avoid the problems of AI, you can change up the recruitment process, in a highly structured, controlled method suggested by Iris Bohnet. It will seem very mechanistic, and it is, deliberately so. The biggest challenge in taking such an approach is that it questions the ‘expertise’ of senior leaders and experienced HR professionals. Are they prepared to take themselves out of the equation? Would they believe an objective process could occur for a decision in which they have an interest, but in which their involvement was limited?

If senior leaders and HR executives are prepared to admit to fallibility, to be aware that they may notice and value the behaviours of different groups of people in different ways, there are emerging practices that will make sure bias is minimised and fairer decisions are made.

Bring the best of the CEOWORLD magazine's global journalism to audiences in the United States and around the world. - Add CEOWORLD magazine to your Google News feed.

Follow CEOWORLD magazine headlines on: Google News, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook.

Copyright 2025 The CEOWORLD magazine. All rights reserved. This material (and any extract from it) must not be copied, redistributed or placed on any website, without CEOWORLD magazine' prior written consent. For media queries, please contact: info@ceoworld.biz